Null-safety Part 1: The Fundamental Problem with Null

The Problem

There are many different types of errors that programmers encounter frequently, which they must guard their programs against. Of those errors, few seem more pervasive than the infamous NullPointerException (NPE), or it’s equivalents. The cause of innumerable bugs and crashes, what programmer has not felt uneasy about the ever-present threat of this bug in their code?

Why is it the case though; that we must always be on the lookout for NPEs? Since software is all about designing reusable abstractions to deal with the complexity of our code; surely this could be handled in a more rigorous and automated way than relying on the diligence of every programmer to check for NPEs in every line of code that they write. There must be a way to solve this problem once and for all, no?

If you look online for explanations as to what causes an NPE, you’ll be met with a plethora of answers. Some of which will give examples of code that will cause an NPE, and others which will simply state the conditions under which an NPE will occur, but few will address the fundamental reason why NPEs are so prevalent, let alone possible in the first place.

I call it my billion-dollar mistake. It was the invention of the null reference in 1965

-Tony Hoare

Null references made their first appearance AGOL W back in 1965, “simply because it was so easy to implement.”, as Tony Hoare recalls. Since then, they’ve become an integral part of many, if not most, mainstream programming languages; however, as Hoare himself admits, the way in which they were implemented lead to the plethora of problems we now associate with NPEs.

The Cause

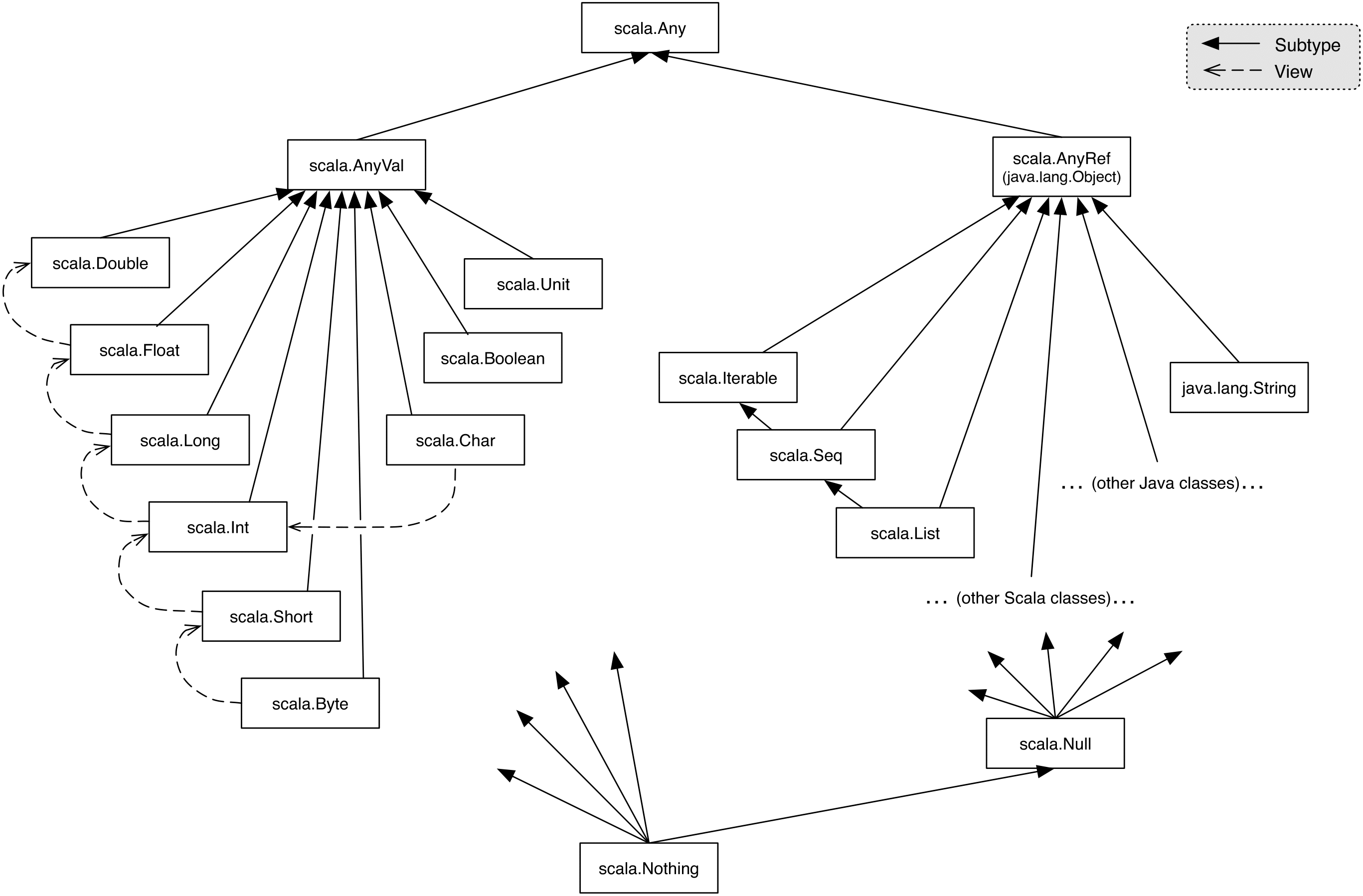

The main reason why NPEs keep popping up is because of a deficiency in the type systems of the languages in which they appear (I’ll expand more on this in the conclusion) and the consequent decision to model null as the same type or a subtype of other values. We’ll use Scala’s type system to study this problem. (Note that all of the conclusions we’ll draw based on this will apply to Java as well, since null works the same in Java.)

This image describes the hierarchy of types within the Scala language. As we can see from the image, null is a subtype of all reference types (AnyRef in Scala, java.lang.Object in Java). This means that null can be used anywhere we’re expecting a reference.

This leads to some issues. Given two references as follows:

val a: String = "hello";

val b: String = null;We can’t tell just by looking at the type signatures which is null and which isn’t; so in a sense, the type system is telling us that these two objects can be used in the same way; but they cannot!

a.substring(2); // "llo"

b.substring(2); // throws NullPointerExceptionSince the whole purpose of static type systems is to understand what can and cannot be done to a certain value at compile time, we can see that conflating non-null and null references is a form of violating static type safety, even if the language doesn’t acknowledge it.

From this perspective, we see that an NPE is similar to the type of error one encounters when calling a method that doesn’t exist on an object in a dynamically typed language; though in the former case, this should be preventable by the type system.

var string = 'Hello'

string.abc() // TypeError: s.abc is not a functionThey’re both instances of calling a method which does not actually exist at runtime.

So this is the fundamental issue: Non-null and null references cannot be treated the same (i.e. have the same type), but many languages do treat them the same.

Another perspective

Another way of looking at this, is through the lens of one of the SOLID principles, the Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP). The LSP is a rule which describes what properties a subtype must have in order to be a valid subtype. There are a few different ways to state the LSP, so I’ll include each of them for whichever makes the most sense to you.

Formally, the LSP states:

Let ϕ ( x ) be a property provable about objects x of type T. Then ϕ ( y ) should be true for objects y of type S where S is a subtype of T.

In object oriented terms:

Functions that use pointers or references to base classes must be able to use objects of derived classes without knowing it.

Yet another way (and perhaps my favorite):

A subtype must possess a superset of the properties of its supertype.

So what the LSP is saying is, because in most languages subtypes can be used anywhere a supertype is expected, attempts to access properties defined in the supertype, must work on the subtype without error.

To use a classic example from OOP textbooks, let’s look at the relationship between a Person and an Employee.

class Person(name: String, age: Int)

class Employee(name: String, age: Int, company: String, salary: Int)

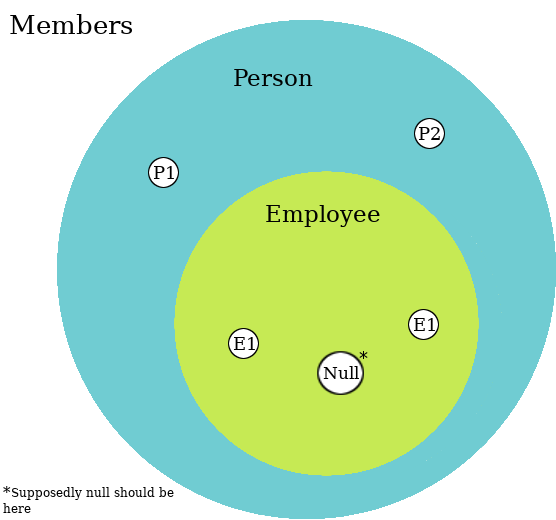

extends Person(name, age)Firstly, let’s look at the set diagram of these classes, for some Persons P1 and P2, and Employees E1 and E2.

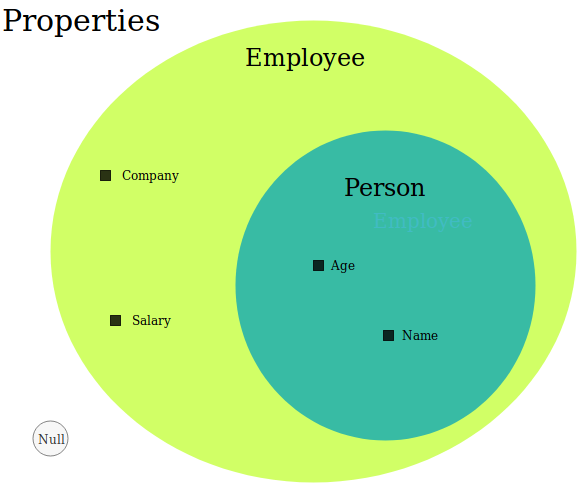

Since null is supposedly a valid subtype of Person and Employee, it belongs inside of the Employee set; but now let’s look at a set diagram of the properties of Person, Employee and null.

Notice that substituting an Employee wherever the program is expecting a Person will work fine, since Employee has a superset of the properties of Person; but do you see the issue with null? This is why null fundamentally should not be modeled as the same type or a subtype. Having null be a subtype of all objects breaks the LSP because null does not possess any properties, let alone a superset of properties. So, when we access a property of an object that is actually null, it doesn’t have that property; thus breaking the LSP and causing an NPE.

The Solution

The solution to this problem is, conceptually, very straight forward; the type system has to keep track of which references are possibly null and which are not. If the type system knew which references were possibly null, then not checking if it were null before using it wouldn’t just be bad practice and an NPE at runtime, but would become an error at compile time; which is exactly what we want.

There are two ways that I know of that this can be implemented:

- A generic wrapper type which would denote a nullable reference, something like C#’s

Nullable<T>, Scala’sOption[T], Rust’sOption<T>, or Kotlin’sT? - A type union of some type

TwithNull, which would look likeT | Null. Typescript can handlenullthis way with the--strictNullChecksflag, and this is also planned for a future version of Scala.

Earlier I mentioned that null being modeled as a subtype of other types was due to a deficiency in the type systems of languages where null is modeled that way. That deficiency is the lack of generics or union types. Without either one of these mechanisms, you can’t create nullable versions of any existing type in the type system.

Conclusion

Modeling null as the same type or subtype of other types in the type system is the problem with the design of null in most languages.

References:

- https://www.infoq.com/presentations/Null-References-The-Billion-Dollar-Mistake-Tony-Hoare

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tony_Hoare

- https://www.scala-lang.org/files/archive/spec/2.12/12-the-scala-standard-library.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Null_pointer

- https://stackoverflow.com/questions/218384/what-is-a-nullpointerexception-and-how-do-i-fix-it

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Subtyping

In the next part, we’ll examine the current strategies for dealing with null safety in Scala today, given the way null works.